It’s been seven years since the global financial crisis of 2008. Although market volatility has picked up somewhat recently, markets have stayed relatively stable. Major world economies, such as the United States, Japan, China, and the Europe Union, remain sluggish, but are mostly reporting positive growth rates.

Are we embarking on a new era of prosperity? Or has the crisis morphed somehow into something altogether different? In short, is the crisis fully behind us? Or should we expect another one to erupt sometime soon? We asked CFA Institute Financial NewsBrief readers what they think the probability is that the world will experience another financial crisis in the next five years.

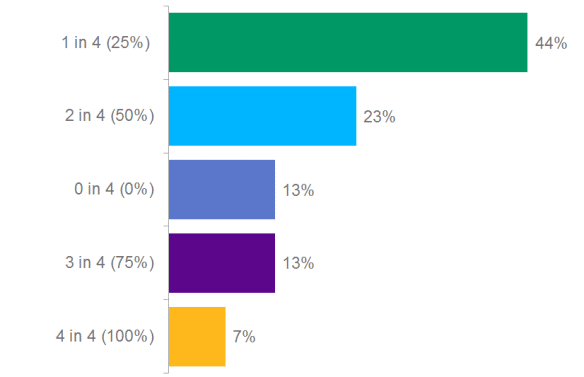

Poll: What are the chances of another global financial crisis occurring in the next five years?

Only 13% believe we won’t experience another major crisis. At the other extreme, 7% believe that an economic cataclysm is imminent. A plurality (44%) of respondents estimate a one-in-four chance that another crisis is on the horizon. About 23% of respondents handicap the odds at 50–50, while 13% put it at three in four.

These responses clearly indicate that the Great Recession has left an indelible mark on the minds of many poll participants and, quite likely, on the market as a whole. So let’s look at some of the key factors in the last crisis and compare them then and now. (This analysis will focus on the United States, the epicenter of the last crisis. I acknowledge, however, that other countries could find themselves at the center of the next crisis.)

With the passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act in 1999, the US Congress effectively repealed the Glass-Steagall Act. This removed the separation of investment and commercial banking and enabled banks to hold more securities, such as subprime mortgage-backed securities. In 2004 the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rule change regarding capital adequacy required the major investment banks to adopt a version of the Basel II risk-weighting approach to capital adequacy. In practice it created mal-incentives for banks to own government bonds, which were given a zero-risk weighting, and triple-A mortgage-backed securities, which had capital requirements commensurate with their ratings. Mortgage-back securities rated AA or AAA only had a capital requirement of 2 cents on the dollar (i.e., leverage of 50-to-1).

In 2010 the Dodd-Frank Act was passed by the US Congress. Accordingly, banks must now meet their capital requirements at the holding company level and not just separately by operating divisions. During the crisis, many banks were able to securitize virtually all exposure to underlying loans. Under Dodd-Frank, 5% of securitized credit must be retained by the securitizer. So the incentives of the originator are now more in line with the security holder.

Between 2000 and 2005, the US Federal Reserve kept interest rates artificially low. These low rates encouraged borrowers to borrow more and banks to make more loans than they otherwise would. The long end of the curve was brought down by a rapidly growing current account deficit in the United States in which foreign trading partners used their US dollars to buy US Treasuries of all maturities. In fact, foreign ownership of US Treasuries skyrocketed from about $1 trillion in 2002 to about $2.1 trillion in 2006. Since the crisis, the central banks have been keeping rates even lower (near zero).

A major factor in the last crisis was, of course, the rapid growth of low-quality mortgages. Between 2000 and 2006, the combination of subprime and Alt-A loans rapidly grew their share of mortgage originations. Since the crisis, subprime alone has fallen from a peak of more than 20% of originations in 2006 to roughly 0.3% as of 2014. However, the spigot has opened elsewhere. Auto loans have grown rapidly to $970 billion. Through the middle of 2014, about 29% of all the securities based on auto loans to individuals were classified subprime, and defaults are now rising. Student loans are not broken out by quality (i.e., subprime), but there are two issues with them that are important to note. First, they have grown rapidly to $1.36 trillion. Moreover, as graduates and younger people are having a difficult time entering the work force,delinquencies on student loans in repayment are an estimated 27.3%. As it happens,the Federal government owns $883 billion (65%) of the student loans, so defaults will lead to more government bond issuances and, ultimately, more inflation. More recently, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) has become much more aggressive with its capital requirements by reducing down payments and credit scores. In fact, many in the mortgage industry are preparing for a subprime resurgence in 2015.

In the wake of the crisis, the United States engaged in a wide range of massive bailouts. These bailouts took the form of both direct purchases of assets and guarantees. Consequently, the bailouts effectively transferred much of the bad debts to the balance sheets of governments worldwide. In response, a wave of money printing through various quantitative easing (QE) measures surged across the world. Whether this tide of new money will advance slowly over time or come crashing down quickly is far from certain. But it will eventually have an impact. Perhaps this is what our astute readers have sniffed out.

The article was first published on blogs.cfainstitute.org